A Case of Cardiac Arrest due to Multivessel, Diffuse Coronary Spasm in Moyamoya Disease

Article information

Abstract

Moyamoya disease is characterized by progressive stenosis of the distal portion of the internal carotid arteries and fragile collateral vessels in the brain. The precise pathogenesis is still not known. Although extracranial vessel involvement is very rare, coronary arterial involvement has recently been reported. Here, we report a case of diffuse, multivessel coronary spasm leading to cardiac arrest and myocardial infarction in a 47-year-old man with moyamoya disease with no underlying emotional or physical stress.

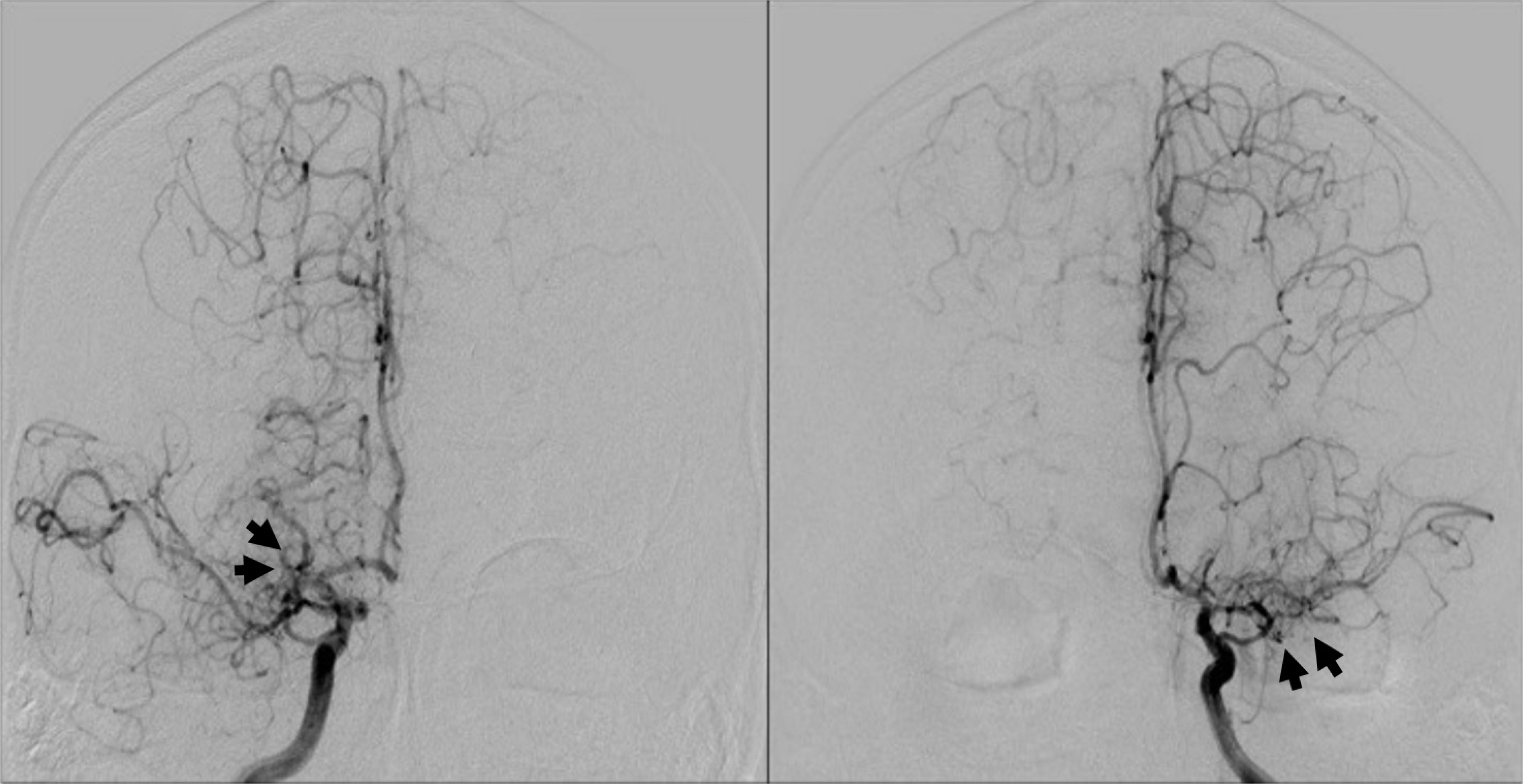

Cerebral angiogram after injection of contrast demonstrates stenosis in both internal carotid arteries, with net-like collaterals (black arrow) typical for moyamoya disease.

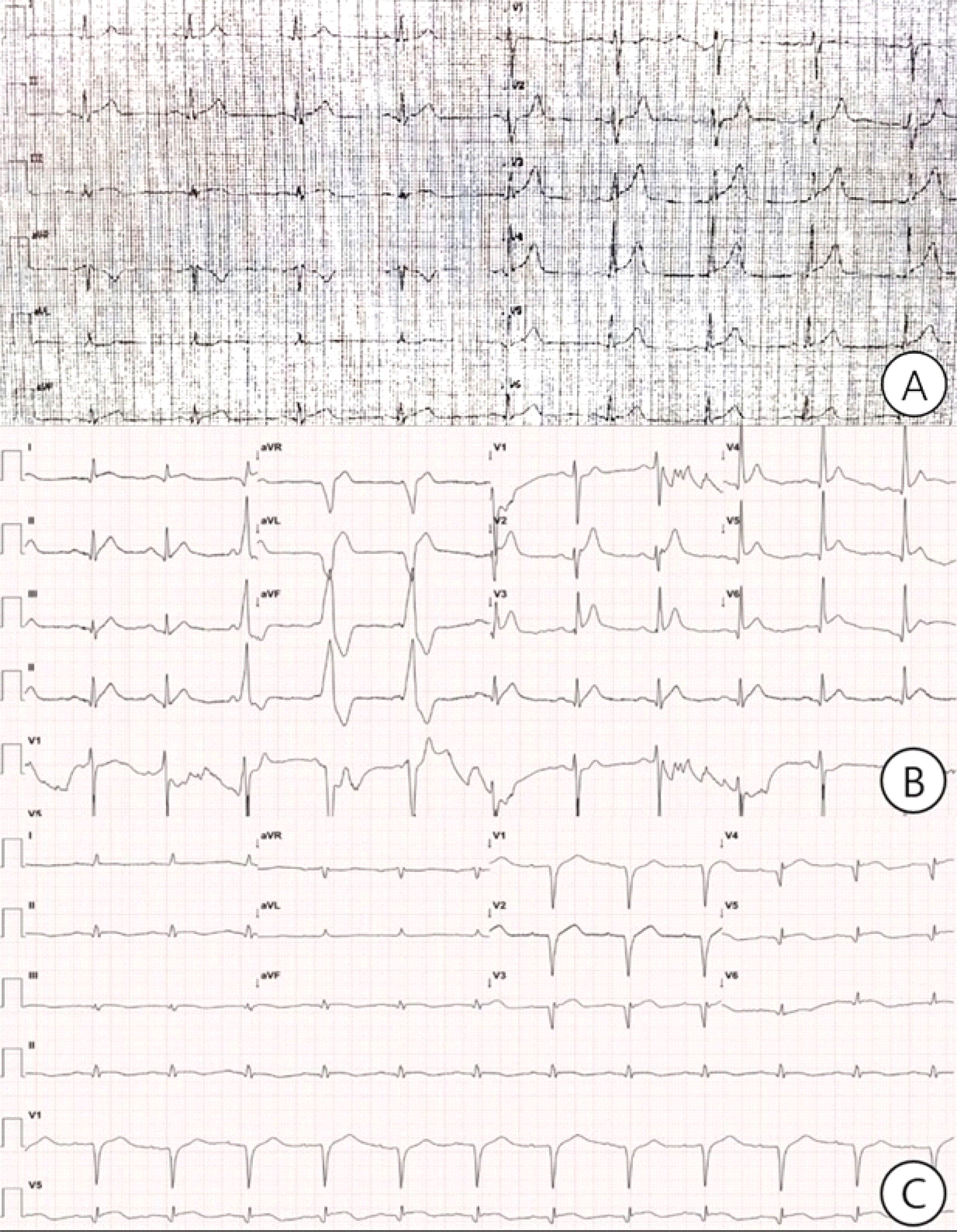

Local hospital ECG 3 years ago for acute chest pain showed ST elevation in leads Ⅱ, Ⅲ, aVF, and V2-V6 (A). ECG after electro-cardioversion: the irregular rhythm converted to sinus rhythm with ST elevation in Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, and V2-6, with frequent ventricular premature complexes (B). Follow-up ECG 5 days later showed ST resolution in Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, and V2-6, and Q waves in V1-5 (C).

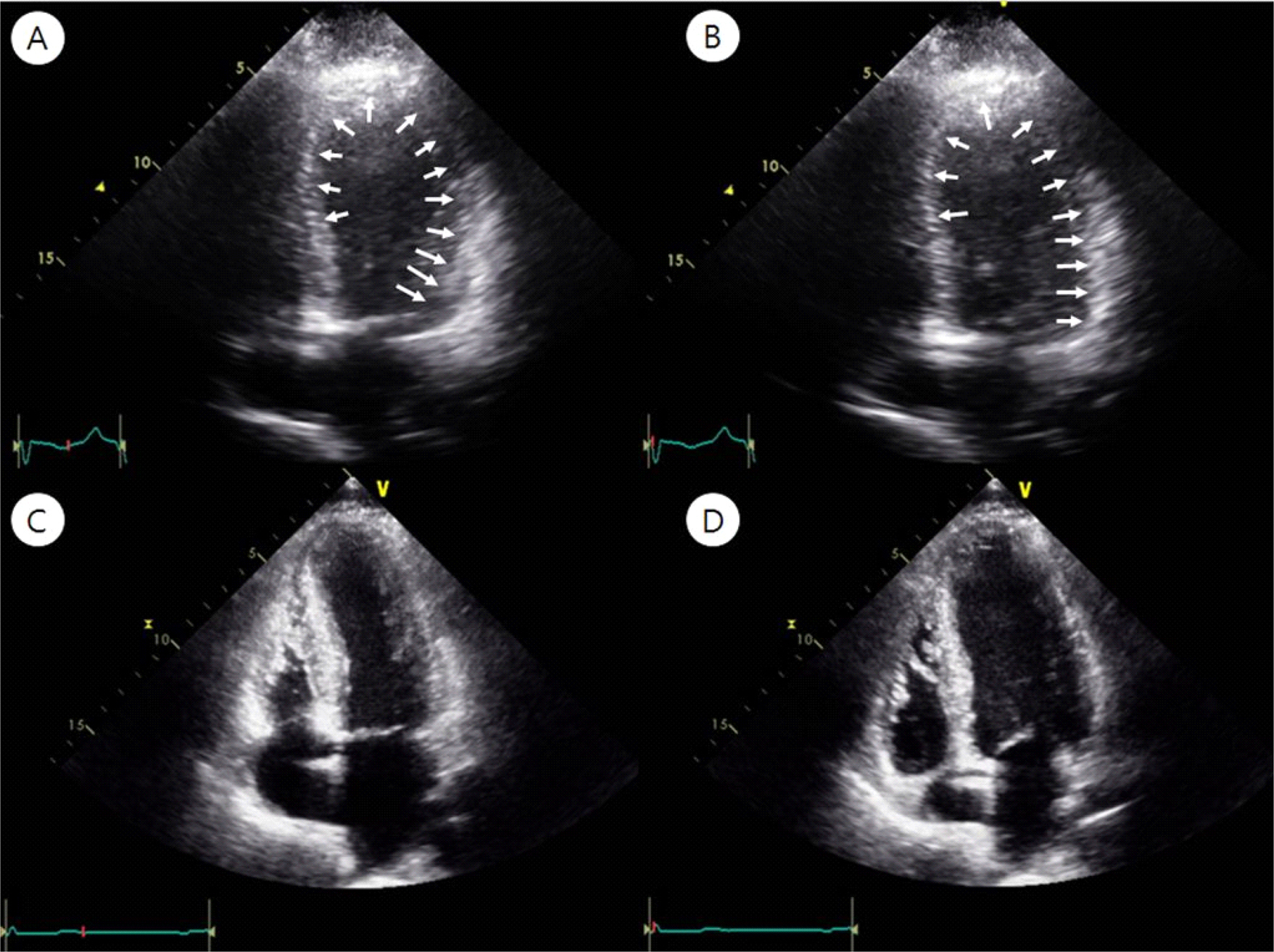

Echocardiography demonstrated akinesis in the entire mid- to apical segments of the left ventricular (LV) wall, with severe LV dysfunction (LV ejection fraction 25%) and mild apical dilatation (white arrow), which suggest stress induced cardiomyopathy (A: systolic phase, B: diastolic phase). Follow up echocardiography demonstrated true apical akinesis, and hypokinesis of the apical anterior septum and anterior LV wall, with improved LV function; LV ejection fraction 45% (C: systolic phase, D: diastolic phase).

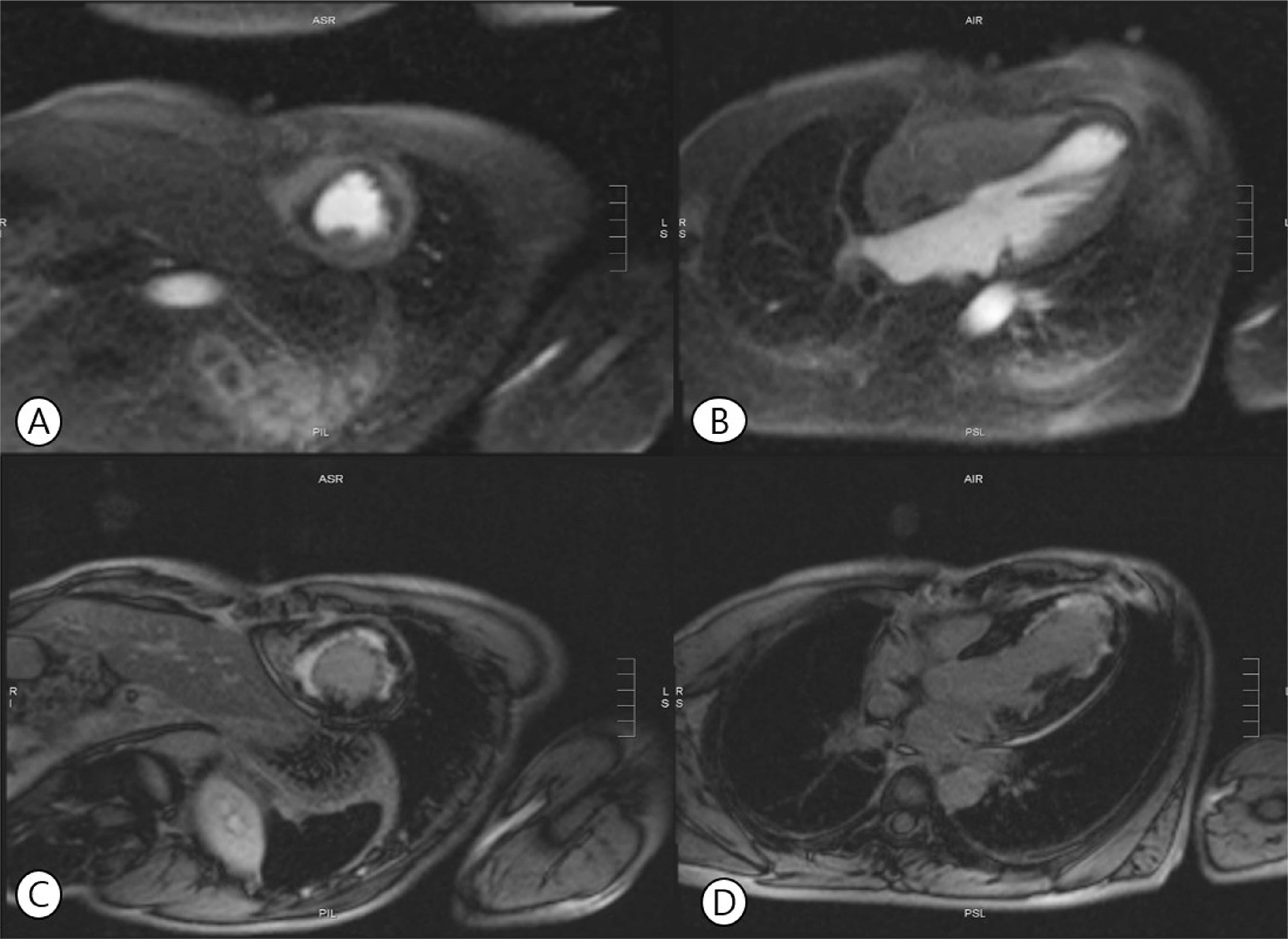

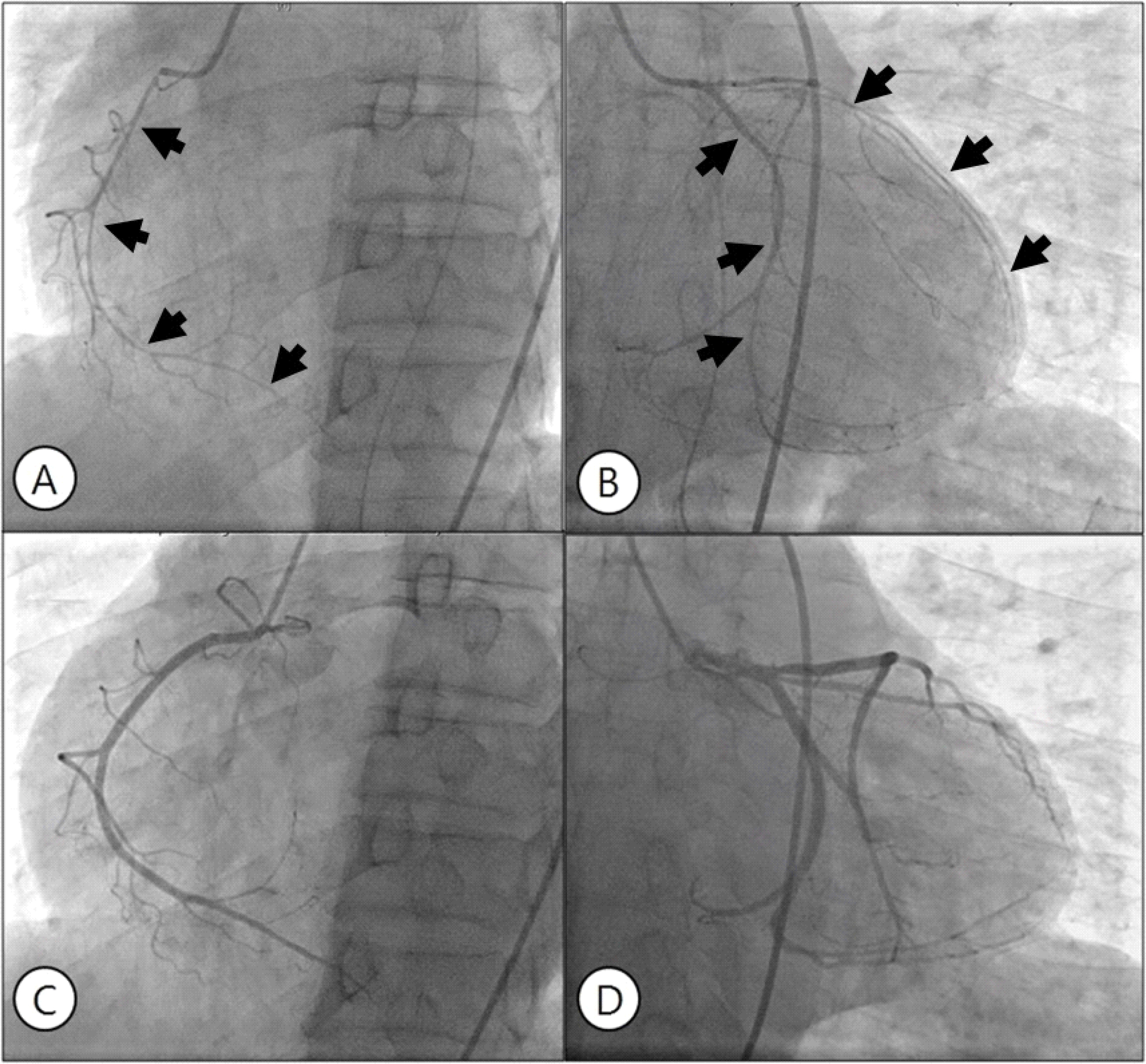

Angiography reveals diffuse spasm of the right (A) and left (B) coronary arteries (black arrow). After intracoronary nitroglycerin injection, spasm was relieved in both coronary arteries (C, D).