Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Kosin Med J > Volume 37(1); 2022 > Article

-

Review article

Sleep and vaccine administration time as factors influencing vaccine immunogenicity -

Eun Seok Kim1,2

, Chi Eun Oh3

, Chi Eun Oh3

-

Kosin Medical Journal 2022;37(1):27-36.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7180/kmj.22.014

Published online: March 29, 2022

1World Vision, Kampala, Uganda

2London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

3Department of Pediatrics, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea

- Corresponding Author: Chi Eun Oh, MD, PhD Department of Pediatrics, Kosin University College of Medicine, 262 Gamcheon-ro, Seo-gu, Busan 49267, Korea Tel: +82-51-990-6121 E-mail: chieunoh@office.kosin.ac.kr

Copyright © 2022 Kosin University College of Medicine.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,749 Views

- 41 Download

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Immune response, circadian rhythm, and sleep

- Animal studies on the influence of circadian rhythms and sleep on the immunogenicity of vaccines

- Human studies on the association between sleep and the immunogenicity of vaccines

- Association between circadian rhythms and the immunogenicity of vaccines

- Immunogenicity of vaccines according to the vaccination time during the day

- Impact of circadian rhythms and sleep on the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines

- Conclusions

- Article information

- References

Abstract

- The immunogenicity of vaccines is affected by host, external, environmental, and vaccine factors; in addition, sleep or circadian rhythms may also have effects. With the use of vaccines to mitigate the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, research is underway to clarify what time of the day is optimal for COVID-19 vaccination and how disturbances of circadian rhythms will affect the immunogenicity of the vaccine in shift workers. Studies on the relationship between sleep time and the immunogenicity of vaccines for influenza and hepatitis have demonstrated that less sleep time and sleep deprivation tended to adversely affect immunogenicity. In some studies, there were even sex differences in these effects. When comparing shift workers with disturbances in their circadian rhythms and those who only worked during the day, one study found less antibody formation in shift workers; however, further studies on the relationship between shift work and the immunogenicity of vaccines are needed. Studies on the relationship between vaccine administration time and immunogenicity have shown different results according to age and sex. Therefore, future studies on vaccine administration time and immunogenicity may require an individualized approach for each vaccine and each population to be vaccinated. There is accumulating evidence on the effects of sleep and vaccine administration time on the immunogenicity of vaccines. However, further studies are needed to determine whether the association between immunogenicity and circadian rhythms and vaccine administration time can be used as a basis to increase the immunogenicity for individual vaccines.

- Vaccination has had a tremendous impact on people’s health worldwide. It was possible to prevent countless people from contracting diseases or dying through vaccination [1].

- Efforts have been made to create an effective and safe vaccine against infectious diseases that threaten people’s health. As people worldwide are being vaccinated owing to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, information on the immunogenicity and safety of the vaccines is of great interest. Several factors influence the immunogenicity of vaccines. For example, there are intrinsic host factors, such as sex, age, immune history, and comorbidities; environmental factors, such as geographic location and season; nutritional factors, such as body mass index; and vaccine factors, such as the type of vaccine antigen, injection route, adjuvant type, and dose [2].

- In addition, sleep or circadian rhythms have been indicated to also affect the immunogenicity of vaccines [3,4]. The circadian rhythm regulates the sleep-wake cycle of the human body, blood pressure, body temperature, daily changes in cortisol production, and immune function [5,6]. Simultaneously, sleep also affects the immune function [5]. Therefore, researchers have studied whether administering vaccines at a specific time of the day will have a positive effect on the immunogenicity of the vaccines and whether sleep affects such immunogenicity [5,7]. Recently, research results on when it is best to administer COVID-19 vaccines have been reported, and research on the immunogenicity of these vaccines in shift workers is ongoing [8,9].

- This review summarizes the results of studies on the effect of sleep or circadian rhythms on the immunogenicity of vaccines. Based on the study findings, we would like to introduce ongoing studies on the relationship between circadian rhythms and immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines.

Introduction

- Most vaccines induce B- and T-cell responses, producing antibodies (humoral immunity) and inducing cellular immunity. Antibodies can specifically bind to toxins or pathogens and directly or indirectly kill infected cells with cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. CD4+ T lymphocytes reduce, regulate, and clear extracellular and intracellular pathogens by assisting B cells, CD8+ T lymphocytes, and macrophages [10].

- The first report by Elmadjian and Pincus [11] in 1946 showed that the number of circulating lymphocytes changed throughout the day. Subsequent studies have shown that circadian rhythms affect the regulation of proinflammatory cytokine secretion. For example, when endotoxins stimulate macrophages, the amount of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) secreted by macrophages shows a circadian pattern according to the injection time of the endotoxin [12]. However, if there is light-dark cycle desynchronization or a defect in a key gene related to the circadian clock, circadian changes in cytokine production cannot be seen in macrophages. Because clock-controlled genes generate circadian patterns for gene expression in cells, the regulation of metabolism and other major pathways is influenced by the time of day [13,14]. Circadian rhythms also regulate leukocyte trafficking. Rhythmic trafficking in both neutrophils and lymphocytes is driven by clocks regulated by leukocytes and endothelial cells surrounding blood vessels [15,16].

- Sleep strengthens innate and adaptive immune responses [17]. Studies have shown that sufficient regular sleep and sleep quality enhance immune function and improve response to vaccines [5]. The secretion of proinflammatory cytokines is increased in cases of experimental sleep deprivation and in people who have a habit of sleeping less, especially men [18,19]. It has been reported that the levels of neutrophils, B lymphocytes, monocytes, and natural killer (NK) cells increase when awake for a long time and decrease after getting enough sleep [7].

- Although circadian rhythms and sleep are different domains, they influence each other. Because of this interaction, the lack of sleep in people with circadian rhythm disturbances may affect the immune function [20].

Immune response, circadian rhythm, and sleep

- Adequate sleep is important for the maintenance of good health in animals. Long-term sleep deprivation in rats has fatal consequences on vitality, and chronic sleep deprivation in animals has led to splenic atrophy and bacteremia [21,22]. There have been several animal studies on the effect of sleep time and vaccine administration time on the efficacy of vaccines. In mice, the response of T lymphocytes to antigens has been reported to exhibit circadian rhythms [23]. The proliferation of T lymphocytes in response to stimulation showed circadian changes, and the tyrosine kinase ZAP70, which plays a key role in T lymphocyte function, also showed rhythmic protein expression [23]. In addition, mice immunized with OVA peptide-loaded dendritic cells (DCs) demonstrated a stronger specific T cell response when immunized during the day than when vaccinated at night. A recent study also showed that when mice were administered DCs loaded with the OVA257–264 peptide antigen (DC-OVA), the CD8+ T cell response was higher when administered in the middle of the day than at other time points [24]. In this study, when the circadian transcriptome of CD8+ T cells was analyzed, it was confirmed that the genes and pathways involved in T cell activation were abundant during daytime.

- The activation of innate immunity is essential for inducing an effective adaptive immune response. Silver et al. [25] evaluated the response to a vaccine when CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN)-adjuvanted immunization was performed after Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 expression and function increased. Antigen-induced proliferation and interferon-gamma production were significantly higher when OVA-CpG ODNs were administered to zeitgeber time (ZT) 19 (nighttime) mice, which had an increased TLR9 response, than when they were administered to ZT7 mice.

- Mice are nocturnal animals; therefore, they are active at night and sleep throughout the day. Based on the results of studies on vaccine administration time and immunogenicity in mice, the response of T cells to the vaccine antigen was higher during the day than at night. However, in an experiment on the expression and function of TLR9, a factor related to innate immunity, the immunogenicity was better when mice were vaccinated using TLR9 ligands as an adjuvant than when they were vaccinated at night.

Animal studies on the influence of circadian rhythms and sleep on the immunogenicity of vaccines

- In human vaccine clinical trials, it has been reported that sleep and shift work patterns affect the immunogenicity of vaccines. Studies on the relationship between sleep duration or sleep deprivation and post-vaccination immunogenicity have mainly been conducted using influenza and hepatitis vaccines. Table 1 summarizes human studies on the relationship between sleep and the immunogenicity of vaccines. Among studies on sleep deprivation and the immunogenicity of vaccines in humans, the earliest results were published in 2002 by Spiegel et al. [26]. In 25 young men with an average age of 23 years, one group of 11 participants slept only 4 hours during the first 6 days, and the other group of 14 participants slept 7.5–8.5 hours as usual. Influenza vaccine was administered on the morning of the 4th day. In the antibody titer measurement 10 days after vaccination, in which the antibody increased logarithmically, the average antibody titer of the sleep-deprived group was less than half of that of the normal sleep group. However, there was no significant difference in the antibody titers between the two groups 3–4 weeks after vaccination. Prather et al. [27] administered influenza vaccine to 83 young adults and asked them to maintain a sleep diary for 13 days before and after vaccination. In their study, the antibody titers to the A/New Caledonia viral strain tested 1 and 4 months after vaccination were lower in those who had a shorter sleep period than in those with a longer sleep period. Lange et al. [28] administered hepatitis A vaccine to 19 adults aged 20–35 years and evaluated the antibody titer 28 days after immunization. Ten participants slept at nighttime as usual on the vaccination day, while nine participants were not allowed to sleep and kept waking for 36 hours on the vaccination day. The hepatitis A vaccine antibody titers were almost twice as high in the participants who slept as usual after vaccination compared with those in the participants who had to remain awake on the day of vaccination. According to the study published in 2011 by Lange et al. [29], in 27 healthy men who were administered hepatitis A and B vaccines and then either slept or stayed awake on the night of vaccination, post-vaccination sleep boosted immunological memory responses compared with staying awake; the number of antigen-specific Th cells increased, and the fraction of Th1 cytokine-producing cells increased when they slept after vaccination. Sleep also significantly increased the antigen-specific IgG1 levels. One study reported that 24 students in their early 20s were administered influenza vaccine in the morning; 13 had their usual sleep in the evening, and 11 stayed awake until 6 PM the next day [30]. Blood was drawn from the participants on days 5, 10, 17, and 52 to measure the hemagglutination-inhibition titers against the H1N1 virus. A decrease in the serum antibody titer was observed on day 5 post-vaccination in men who could not sleep after vaccination compared with that in those who slept normally. However, there was no difference in the antibody titers between the two groups among women. In addition, there was no difference in the antibody titers between the two groups on days 10, 17, and 52 after vaccination, except on day 5 after vaccination. In this previous study, temporary sleep deprivation was not expected to have a lasting effect on the formation of antibodies against influenza vaccine. Further studies are needed to understand why the effects of sleep deprivation on antibody formation differ between men and women. Prather et al. [31] administered hepatitis B vaccine three times to healthy adults aged 40–60 years to determine whether sleep time affects the production of antibodies to the vaccine antigen. They used actigraphy and electronic sleep diaries to measure the sleep time. Actigraphy was used to measure sleep time and sleep efficiency for 6 consecutive days, 3 days before and 3 days after the first vaccination. A shorter sleep duration resulted in lower secondary antibody response. Shorter sleep was also associated with a lower rate of reaching an antibody titer that would be clinically protective against hepatitis B after completion of the third vaccination.

- Considering the results of several studies on the relationship between antibody formation for specific antigens after vaccination and sleep, lesser sleep times or sleep deprivation before and after vaccination negatively affected the immunogenicity of vaccines, except for one study that showed no differences in the antibody titer regardless of sleep deprivation in women [30].

Human studies on the association between sleep and the immunogenicity of vaccines

- Shift workers are an essential group in studies on sleep and circadian rhythms and their relationship to immunity. Therefore, studies have been conducted on changes in immune cells and responses to vaccines in shift workers. In a study of Norwegian nurses, the authors aimed to evaluate differences in immunological biomarkers depending on the work schedule, sleep time, and shift work [32]. However, the work schedule, the number of night shifts, a short sleep duration, and a poor sleep quality did not affect the levels of immunological biomarkers. Therefore, it was not possible to conclude on how shift work affected the immunity in their study. However, when the biomarker levels were compared after a night of sleep with those after a night or day shift, the interleukin (IL)-1 beta levels were higher both after a night shift and day shift than after a night of sleep. The TNF-α levels were higher after a day shift than after a night of sleep. The monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 levels were lower after a night shift and day shift than after a night of sleep. These findings suggest that shift work can acutely affect the immune function. In a study that simulated a 4-day night shift protocol and evaluated its effect on circadian regulation of the human transcriptome, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected through two blood sample collections [33]. In the night shift condition, rhythmic transcripts were significantly reduced compared with the baseline. Upon further analysis, the rhythmicity was not completely lost owing to the night shift condition; rather, the rhythm was dampened. Functional analysis showed that the immune response mediated by NK cells and the Jun/AP1 and STAT pathways were mainly affected by night shift work.

- A recent study examined 34 workers aged 22–59 years who worked night or day shifts to determine whether night shifts affected the immune responses after vaccination [34]. After the polysomnography test, meningococcal C meningitis vaccine was administered to the participants the following day. The researchers evaluated humoral and cellular immune responses after vaccination. In night shift workers, the levels of inflammatory mediators TNF-α and IL-6 increased before vaccination. In addition, the antibody titers measured on days 28 and 56 of vaccination in night shift workers were significantly lower than those in day workers. The CD4+ T cell count, plasmacytoid DC count, and prolactin level decreased among night shifters, and the Treg cell count increased in those with low antibody titers. Alterations in sleep and circadian rhythms were also associated with decreased antibody responses. The post-vaccination humoral response decreased when night shift-related phase delay was prolonged.

- Researchers continue to argue whether shift workers are at an increased risk of developing cancer, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes [35]. Disturbance of circadian rhythms owing to shift work seems likely to affect immune cells and responses, and the effects may consequently cause changes in the immune response after vaccination.

Association between circadian rhythms and the immunogenicity of vaccines

- Because the immune system is known to have a circadian rhythm, there have also been studies on the relationship between the vaccine administration time and immunogenicity of vaccines [36,37]. Table 2 presents studies on the relationship between the vaccination time and immunogenicity of vaccines. In the study by Long et al. [38] conducted in the UK, 276 adults aged ≥65 years were divided into two groups: one vaccinated with influenza vaccine in the morning (9–11 AM) and the other group in the afternoon (3–5 PM). The antibody titers against influenza A (H1N1) and B strains were higher in the morning immunization group than in the afternoon immunization group. The antibody response to influenza vaccination in elderly people is a crucial issue but was impressive in this previous study, because it showed the possibility of increasing the effects of influenza vaccination in this population. The antibody response can be increased by simply setting the vaccination time in the morning.

- Karabay et al. [39] subdivided 65 participants aged 19–23 years into two groups: one group received hepatitis B vaccine in the morning and the other group in the afternoon. There was no difference in the immune responses between the two groups.

- Phillips et al. [40] performed two studies on the vaccine administration time and antibody responses. In their first study on hepatitis A vaccine in 75 students (mean age, 22.9 years), 39 students were vaccinated in the morning and 36 in the evening. In their second study on influenza vaccine in 99 elderly people (mean age, 73.1 years), 59 were vaccinated between 8 and 11 AM and 30 between 1 and 4 PM. The antibody responses to hepatitis A and A/Panama influenza strains were higher in men vaccinated in the morning than in those vaccinated in the evening. However, this was not observed in women. Further studies are needed to determine the reasons for the different antibody responses by sex.

- Gottlob et al. [41] observed whether morning or evening vaccination of neonates affected the cardiorespiratory event rate. They administered the first hexavalent primary vaccine to neonates with 26–30 weeks of gestational age in the morning or evening, counting the episodes of hypoxemia and bradycardia. In addition, they measured the antibody titers against vaccine antigens in each group. There was no difference in the cardiorespiratory event rate between the morning and evening groups, and the antibody titer to Bordetella pertussis increased from baseline in both groups; however, a significant increase in the antibody titer to Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) was observed only in the evening group. However, since the antibody response to Hib was lower in premature babies than in full-term infants in previous studies, one of the reasons for the lower antibody response to Hib in the babies participating in their study may be that the study group included premature babies. The investigators also compared pre- and post-vaccination antibody levels within groups but did not compare the antibody titers between the morning and evening groups. Therefore, based on these results, morning or evening vaccination in premature infants is considered to have no significant effect on the antibody titer or cardiorespiratory event rate. However, the results should be accepted because newborns spend most of their days sleeping, and it is difficult to determine whether they have a circadian rhythm set as in adults.

Immunogenicity of vaccines according to the vaccination time during the day

- As people worldwide become eligible for vaccination owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is increasing interest in the immunogenicity and safety of vaccines. Based on the results of previous studies on the relationship between sleep or vaccine administration time and vaccine efficacy, there were opinions that these factors should be considered in clinical studies on the efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine [42,43]. In a study of 2,784 healthcare workers in the UK, they received either the Pfizer or AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine [8]. There were three categories of vaccination time: time 1, 7:00-10:59 AM; time 2, 11:00 AM–14:59 PM; and time 3, 15:00-21:59 PM. The antibody titers were higher in those vaccinated later when the time 1 group was compared with the time 2 and 3 groups. In this previous study, there were limitations to the interpretation of the results because there was no information on the participants’ medical history, sleeping hours, and shift work patterns that could affect the immunogenicity of the vaccines. However, in the study by Zhang et al. [44], 63 medical personnel were divided into 33 and 30 groups, respectively, and administration of an inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 vaccine (BBIBP-CorV; Sinopharm, Beijing, China) in the morning (9–11 AM) and afternoon (3–5 PM) showed opposite results. Those vaccinated in the morning had stronger B and follicular helper T cell responses than those vaccinated in the afternoon. In addition, those vaccinated in the morning had significantly higher serum neutralizing antibody titers than those vaccinated in the afternoon. In a British study, the antibody titer was high in the afternoon group, while in a Chinese study, the antibody titer was high in the morning group. These two studies administered different types of vaccines and had different study designs; therefore, direct comparison of the results is limited.

- A study on the relationship between the immune response to COVID-19 vaccines and sleep and shift work is ongoing [9]. The researchers noted that in previous influenza and hepatitis vaccine studies, sleep deprivation adversely affected the immunogenicity of the vaccines. Therefore, they hypothesized that there might be differences in the antibody response between shift workers and day workers, as circadian rhythm disturbances and sleep deprivation in shift workers could negatively affect their antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccines.

Impact of circadian rhythms and sleep on the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines

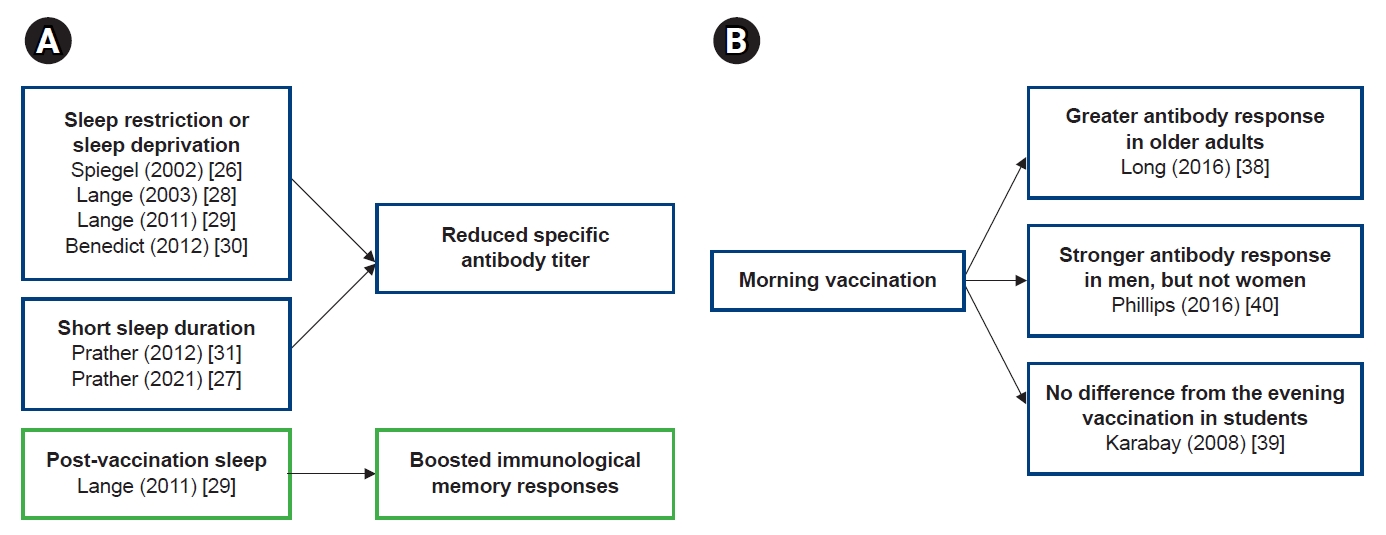

- In studies of the relationship between sleep and vaccine immunogenicity, sleep restriction, sleep deprivation, or less sleep reduced antibody responses to vaccine antigens (Fig 1A). Conversely, sleep after vaccination boosted the immune memory response. Considering the effect of the circadian rhythm on the immune response, it is an interesting topic, presumably related to the time of vaccination and the efficacy of the vaccine. However, there have been few studies on this issue so far, and since the study designs were different, it is difficult to draw consistent conclusions from these study results (Fig 1B). In particular, in the relationship between vaccine administration time and vaccine efficacy, the results according to gender and age were different, and additional research is needed on this. First of all, it should be investigated whether the vaccine administration time really affects the vaccine efficacy, and if so, what mechanism works to make it happen. In addition to the antibody response, studies on sleep and vaccine efficacy should be added to cell-mediated immunity.

- The two most important factors when applying a new vaccine to a specific population are safety and efficacy based on immunogenicity. We can infer from studies on the effects of sleep and circadian rhythms on immune cells and mechanisms that they can also affect the immunogenicity of vaccines; many researchers have already conducted studies to prove this. It is necessary to further understand the role of sleep and vaccine administration time in the adaptive immune responses that directly affect the immunogenicity of vaccines. Through such, it will be possible to determine the appropriate time to administer vaccines and whether intervention for shift workers is necessary when vaccinated.

Conclusions

-

Conflicts of interest

Eun Seok Kim and Chi Eun Oh are editorial board members of the journal but were not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: CEO. Data curation: CEO. Formal analysis: ESK, CEO. Funding acquisition: none. Methodology: ESK, CEO. Project administration: CEO. Visualization: ESK, CEO. Writing - original draft: ESK, CEO. Writing - review & editing: ESK, CEO. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Article information

| First author (year) | Vaccine | Mean age (yr) | No. of participants (% of men) | Study design | Measurements | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiegel (2002) [26] | Influenza vaccine | 23 | 25 (100) | Sleep restriction (n=11) | Antibody titer 10 days and 3–4 weeks after vaccination | The average antibody titer 10 days after vaccination in the sleep-deprived group was less than half of that in the normal sleep group. |

| Normal sleep time (n=14) | There was no significant difference in the antibody titer between the two groups 3–4 weeks after vaccination. | |||||

| Lange (2003) [28] | HAV | Range: 20–35 | 19 (47) | Sleep deprivation on the night of vaccination (n=9) | Antibody titer 28 days after vaccination | The antibody titers were almost twice as high in those who normally slept after vaccination compared with the titers of those who were awake the night after vaccination. |

| Normal sleep (n=10) | ||||||

| Lange (2011) [29] | HAV and HBV | 26.1 | 27 (100) | Sleep deprivation on the night of vaccination (n=14) | Ag-specific Th cell response and HAV- and HBs-specific Ab | Post-vaccination sleep boosted the development of the Th1 immune response. |

| Normal sleep (n=13) | Sleep enhanced the HAV and HBV-specific IgG1 response. | |||||

| Benedict (2012) [30] | Influenza A and H1N1 virus vaccine | Sleep deprivation group: 20.4 | 24 (46) | Sleep deprivation (n=11) | Specific antibody titer on days 5, 10, 17, and 52 following vaccination | In comparison to the sleep group, the sleep-deprived male group but not the female group had reduced antibody titers 5 days after vaccination. |

| Sleep group: 20.6 | Normal sleep (n=13) | There was no difference in antibody titers at later time points between the sleep group and the sleep-deprived group. | ||||

| Prather (2012) [31] | HBV | 50.1 | 125 (44) | No intervention | (1) Sleep efficiency (actigraphy-derived), sleep duration (diary-based), or subjective sleep quality | A shorter sleep duration was associated with a lower antibody response to vaccination. |

| (2) Blood sample collection: before the second and third vaccinations and 6 months after the last dose | Sleep efficiency and sleep quality were generally not related to the magnitude of the antibody response to HBV. | |||||

| Prather (2021) [27] | Influenza vaccine | 18.3 | 83 (44) | 13 Days of sleep diaries and administration of influenza vaccine on day 3 of the study | Antibodies to the A/New Caledonia viral strain 1 and 4 months after vaccination | A shorter sleep duration on the two nights before the vaccination was associated with fewer antibodies 1 and 4 months after vaccination. |

| First author (year) | Vaccine | Age (yr) | No of participants (% of women) | Study design | Measurement | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long (2016) [38] | Influenza vaccine | ≥65 | 276 (49) | Morning vaccination: 9–11 AM | (1) Antibody titers: pre- and post- (1 month) vaccination | The participants vaccinated in the morning had a greater antibody response than those vaccinated in the afternoon. |

| Afternoon vaccination: 3–5 PM | (2) Serum cytokine and steroid hormone levels at baseline | The cytokine and steroid hormone levels were not related to the antibody responses. | ||||

| Karabay (2008) [39] | Hepatitis B vaccine | 19–23 | 63 (57) | Morning vaccination (n=30) | Anti-HBs titers: 1 month after the final vaccination | After three doses of vaccine, there was no difference in the geometric mean antibody titers between the morning vaccination group and the evening vaccination group. |

| Evening vaccination (n=33) | ||||||

| Phillips (2008) [40] | Study 1: hepatitis A vaccine | Study 1: mean age of 22.9 | Study 1: 75 (55) | Study 1: morning (n=39) or evening (n=36) vaccination | Antibody titers: pre- and post- (1 month) vaccination | Men, but not women, vaccinated in the morning showed a stronger antibody response to HAV and influenza vaccines than men vaccinated in the afternoon. |

| Study 2: influenza vaccine | Study 2: mean age of 73.1 | Study 2: 89 (57) | Study 2: time of day of vaccination-an opportunistic variable. A binary AM (n=59)/PM (n=30) variable was created. | |||

| Gottlob (2019) [41] | Hexavalent vaccine | Gestational age at birth: 26–30 weeks | 26 (58) | Morning vaccination (n=12) | (1) CER: episodes of hypoxemia or bradycardia | There was no impact of morning or evening vaccination on the CER. |

| Evening vaccination (n=14) | (2) Antibody titers for pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae type b at a corrected age of 3 months | Vaccination led to an increase in the CER in both groups; however, there was no difference in the CER between the morning and evening groups. | ||||

| The antibody titers for Bordetella pertussis increased in both groups, with no difference in the levels of inflammatory markers 24 hours after vaccination. |

- 1. Plotkin SL, Plotkin SA. A short history of vaccination. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, editors. Vaccines. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc.; 2013. p. 1–13.

- 2. Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Factors that influence the immune response to vaccination. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019;32:e00084–18.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Cermakian N, Stegeman SK, Tekade K, Labrecque N. Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity and vaccination. Semin Immunopathol 2022;44:193–207.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Downton P, Early JO, Gibbs JE. Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity. Immunology 2020;161:268–77.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Haspel JA, Anafi R, Brown MK, Cermakian N, Depner C, Desplats P, et al. Perfect timing: circadian rhythms, sleep, and immunity: an NIH workshop summary. JCI Insight 2020;5:e131487.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Refinetti R. Integration of biological clocks and rhythms. Compr Physiol 2012;2:1213–39.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haack M. The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2019;99:1325–80.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Wang W, Balfe P, Eyre DW, Lumley SF, O’Donnell D, Warren F, et al. Time of day of vaccination affects SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in an observational study of health care workers. J Biol Rhythms 2022;37:124–9.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Lammers-van der Holst HM; Lammers GJ, van der Horst GT, Chaves I, de Vries RD, GeurtsvanKessel CH, et al. Understanding the association between sleep, shift work and COVID-19 vaccine immune response efficacy: protocol of the S-CORE study. J Sleep Res 2022;31:e13496.PubMed

- 10. Siegrist CA. Vaccine immunology. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, editors. Vaccines. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc.; 2013. p. 14–32.

- 11. Elmadjian F, Pincus G. A study of the diurnal variations in circulating lymphocytes in normal and psychotic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1946;6:287–94.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Keller M, Mazuch J, Abraham U, Eom GD, Herzog ED, Volk HD, et al. A circadian clock in macrophages controls inflammatory immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:21407–12.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Scheiermann C, Gibbs J, Ince L, Loudon A. Clocking in to immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2018;18:423–37.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. The meter of metabolism. Cell 2008;134:728–42.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Oishi K, Ohkura N, Kadota K, Kasamatsu M, Shibusawa K, Matsuda J, et al. Clock mutation affects circadian regulation of circulating blood cells. J Circadian Rhythms 2006;4:13.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Zhao Y, Liu M, Chan XY, Tan SY, Subramaniam S, Fan Y, et al. Uncovering the mystery of opposite circadian rhythms between mouse and human leukocytes in humanized mice. Blood 2017;130:1995–2005.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Irwin MR. Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health. Nat Rev Immunol 2019;19:702–15.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Mullington JM, Simpson NS, Meier-Ewert HK, Haack M. Sleep loss and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;24:775–84.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Richardson MR, Churilla JR. Sleep duration and C-reactive protein in US adults. South Med J 2017;110:314–7.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. J Neurosci 1995;15(5 Pt 1):3526–38.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Rechtschaffen A, Gilliland MA, Bergmann BM, Winter JB. Physiological correlates of prolonged sleep deprivation in rats. Science 1983;221:182–4.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Everson CA. Sustained sleep deprivation impairs host defense. Am J Physiol 1993;265(5 Pt 2):R1148–54.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Fortier EE, Rooney J, Dardente H, Hardy MP, Labrecque N, Cermakian N. Circadian variation of the response of T cells to antigen. J Immunol 2011;187:6291–300.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Nobis CC, Dubeau Laramee G, Kervezee L, Maurice De Sousa D, Labrecque N, Cermakian N. The circadian clock of CD8 T cells modulates their early response to vaccination and the rhythmicity of related signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:20077–86.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Silver AC, Arjona A, Walker WE, Fikrig E. The circadian clock controls Toll-like receptor 9-mediated innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity 2012;36:251–61.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Spiegel K, Sheridan JF, Van Cauter E. Effect of sleep deprivation on response to immunization. JAMA 2002;288:1471–2.Article

- 27. Prather AA, Pressman SD, Miller GE, Cohen S. Temporal links between self-reported sleep and antibody responses to the influenza vaccine. Int J Behav Med 2021;28:151–8.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Lange T, Perras B, Fehm HL, Born J. Sleep enhances the human antibody response to hepatitis A vaccination. Psychosom Med 2003;65:831–5.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Lange T, Dimitrov S, Bollinger T, Diekelmann S, Born J. Sleep after vaccination boosts immunological memory. J Immunol 2011;187:283–90.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Benedict C, Brytting M, Markstrom A, Broman JE, Schioth HB. Acute sleep deprivation has no lasting effects on the human antibody titer response following a novel influenza A H1N1 virus vaccination. BMC Immunol 2012;13:1.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Prather AA, Hall M, Fury JM, Ross DC, Muldoon MF, Cohen S, et al. Sleep and antibody response to hepatitis B vaccination. Sleep 2012;35:1063–9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Bjorvatn B, Axelsson J, Pallesen S, Waage S, Vedaa O, Blytt KM, et al. The association between shift work and immunological biomarkers in nurses. Front Public Health 2020;8:415.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Kervezee L, Cuesta M, Cermakian N, Boivin DB. Simulated night shift work induces circadian misalignment of the human peripheral blood mononuclear cell transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:5540–5.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Ruiz FS, Rosa DS, Zimberg IZ, Dos Santos Quaresma MV, Nunes JO, Apostolico JS, et al. Night shift work and immune response to the meningococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy workers: a proof of concept study. Sleep Med 2020;75:263–75.ArticlePubMed

- 35. Wang XS, Armstrong ME, Cairns BJ, Key TJ, Travis RC. Shift work and chronic disease: the epidemiological evidence. Occup Med (Lond) 2011;61:78–89.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 36. Langlois PH, Smolensky MH, Glezen WP, Keitel WA. Diurnal variation in responses to influenza vaccine. Chronobiol Int 1995;12:28–36.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Pollman L, Pollman B. Circadian variations of the efficiency of hepatitis b vaccination. Annu Rev Chronopharmacol 1988;5:45–8.

- 38. Long JE, Drayson MT, Taylor AE, Toellner KM, Lord JM, Phillips AC. Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: a cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine 2016;34:2679–85.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Karabay O, Temel A, Koker AG, Tokel M, Ceyhan M, Kocoglu E. Influence of circadian rhythm on the efficacy of the hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccine 2008;26:1143–4.ArticlePubMed

- 40. Phillips AC, Gallagher S, Carroll D, Drayson M. Preliminary evidence that morning vaccination is associated with an enhanced antibody response in men. Psychophysiology 2008;45:663–6.ArticlePubMed

- 41. Gottlob S, Gille C, Poets CF. Randomized controlled trial on the effects of morning versus evening primary vaccination on episodes of hypoxemia and bradycardia in very preterm infants. Neonatology 2019;116:315–20.ArticlePubMed

- 42. Benedict C, Cedernaes J. Could a good night’s sleep improve COVID-19 vaccine efficacy? Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:447–8.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 43. Liu Z, Ting S, Zhuang X. COVID-19, circadian rhythms and sleep: from virology to chronobiology. Interface Focus 2021;11:20210043.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 44. Zhang H, Liu Y, Liu D, Zeng Q, Li L, Zhou Q, et al. Time of day influences immune response to an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res 2021;31:1215–7.ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KOSIN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MEDICINE

KOSIN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MEDICINE

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite